Pompeii, a city frozen in time, offers a unique glimpse into the everyday life of ancient Rome. Located near the modern city of Naples in Italy, Pompeii was a thriving Roman city until it was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. The city’s sudden burial preserved it for centuries, allowing archaeologists to uncover remarkably well-preserved buildings, artifacts, and even human remains. This preservation provides unparalleled insight into the urban planning, architecture, and daily routines of a Roman city, making Pompeii one of the most significant archaeological sites in the world.

Pompeii’s history dates back to the Bronze Age, around the 8th century BCE, when it was initially established by the Oscans, an ancient Italic people. Over the centuries, it fell under the influence of various cultures, including the Etruscans and Greeks, before becoming a Roman colony in the 4th century BCE. By the 1st century BCE, Pompeii had grown into a bustling urban center, strategically located near the Bay of Naples, which facilitated trade and commerce. The city flourished economically and culturally, becoming known for its luxurious villas, sophisticated infrastructure, and vibrant social life.

The Greeks in Campania (740 BC – 6th century BC)

Pompeii first emerged on the map around 740 BC when the Greeks in Campania arrived, marking the city as significant to the Hellenic people. One of the most notable structures from this period is the Doric Temple, now known as the Triangular Forum. By the 6th century BC, the city was surrounded by an impressive tufa city wall, indicating the wealth of its residents, likely due to flourishing maritime trade. During this time, the Etruscans also settled in the surrounding areas and began controlling the military, integrating Pompeii into the Etruscan League of Cities. The Etruscans contributed to the city’s development by constructing the Temple of Apollo, a primitive forum, and several houses. However, their dominance was short-lived as the Greek city of Cumae and Syracuse defeated the Etruscans in the Battle of Cumae in 474 BC.

The Samnite Period (450 BC – 2nd century BC)

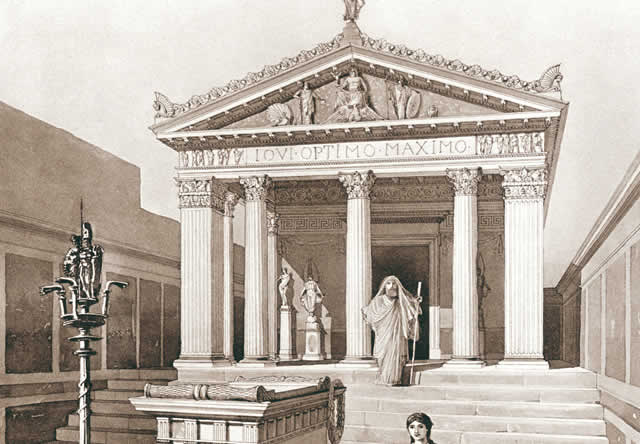

The Samnite period marked a time of transition and development for Pompeii. Many areas of the city were abandoned, but the Samnites took over Greek Cumae and introduced new architectural styles. The Samnite Wars (343 BCE – 341 BCE) saw the Romans entering Campania, bringing Pompeii into Roman orbit while it was still ruled by the Samnites. Despite political instability, the city remained loyal to Rome during subsequent conflicts, such as the Third Samnite War, the Second Punic War, and the war against Pyrrhus. Pompeii’s status as a socii (ally) of Rome was established, fostering continued prosperity. Significant buildings such as the Forum, the Temple of Jupiter, the Large Theatre, the Basilica, and the Stabian Baths were constructed during this period, reflecting the city’s growth and wealth.

The Roman Period (89 BC – 59 AD)

During the Roman Empire, Pompeii was a prosperous city, benefitting from its strategic location and fertile land. The city was an important hub for trade and commerce, connecting different parts of the empire. Public buildings, such as the amphitheater, baths, and forum, reflected the wealth and cultural sophistication of the city. The influence of Roman politics, economics, and culture is evident in the architectural and social fabric of Pompeii. Pompeii’s Roman period began with its involvement in the Social Wars, where it was one of the Campanian towns that rebelled against Rome. After Sulla’s conquest in 89 BC, Pompeii was declared a Roman colony, and its residents were granted citizenship. Latin became the dominant language, and many aristocrats Latinized their names to show support for the new regime. This period saw significant construction and renovation, including the establishment of farms and villas like the Villa of the Mysteries and Villa of Diomedes. Pompeii became a cultural center with new structures such as the Forum Baths, the Amphitheatre of Pompeii, and the Odeon. However, a riot in 59 AD led to a decade-long ban on events at the amphitheater, highlighting the city’s social tensions.

Earthquake of 62 CE

In 62 CE, Pompeii experienced a devastating earthquake that caused significant damage to the city’s infrastructure and buildings. The earthquake destroyed many structures, including temples, homes, and public buildings, prompting a period of extensive reconstruction. Despite the extensive damage, the city remained vibrant, and efforts to rebuild reflected the resilience and resourcefulness of its inhabitants. This disaster, however, foreshadowed the more catastrophic event that would occur 17 years later.

Eruption in 79 CE

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE was a catastrophic event that buried Pompeii under a thick layer of volcanic ash and pumice. The rapid burial preserved buildings, artifacts, and even the impressions of bodies, providing a snapshot of life at the moment of disaster. The suddenness of the eruption caught many residents by surprise, leaving a haunting record of their final moments.

Literary evidence of the eruption primarily comes from Pliny the Younger, who witnessed the event from a distance and later described it in letters to the historian Tacitus. Pliny’s accounts provide a detailed narrative of the eruption’s progression and its impact on the surrounding areas. His descriptions of the eruption’s phases, the behavior of the volcanic cloud, and the panic among the populace are invaluable historical documents that complement the archaeological findings.

Archaeological excavations in Pompeii have uncovered a wealth of evidence about the city’s layout, architecture, and daily life. The preservation of buildings, streets, and artifacts offers a detailed look at Roman urban planning and domestic life. Frescoes, mosaics, and graffiti found on walls provide insights into the artistic expression and social interactions of Pompeii’s residents. The discovery of skeletal remains and casts of bodies further reveals the human tragedy of the eruption, adding a poignant dimension to the archaeological narrative.

First Discoveries and Early Archaeologists

The ruins of Pompeii were first discovered in the late 16th century by the architect Domenico Fontana. Despite this initial discovery, systematic exploration did not begin until the 18th century. The excavation of Herculaneum in 1709 spurred interest in similar archaeological sites, leading to the commencement of excavations at Pompeii in 1748 under the direction of the Spanish engineer Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre. Early excavations were often haphazard and driven by the desire to uncover valuable artifacts, leading to significant looting and loss of context. Despite these early challenges, the discoveries sparked widespread interest in the ancient city and laid the groundwork for more scientific approaches to archaeology.

The early archaeologists who worked in Pompeii were instrumental in developing methods for excavation and preservation. Giuseppe Fiorelli, who directed excavations in the mid-19th century, introduced innovative techniques such as the use of plaster casts to capture the forms of victims and wooden structures. By carefully pouring plaster into these cavities, Fiorelli was able to produce detailed molds of the victims, capturing their final moments with haunting precision. This method provided a poignant glimpse into the human tragedy of Pompeii. Fiorelli also implemented a more systematic approach, dividing Pompeii into nine regions, numbering the insulae (blocks) within each region, and assigning numbers to each door on the streets. This allowed for precise location identification. Fiorelli’s systematic approach and emphasis on recording and preserving findings marked a significant advancement in archaeological practice, setting standards that are still followed today.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, excavations at Pompeii have continued, revealing new insights and expanding our understanding of Roman life. Intensive excavation resumed in 1951 after the interruption caused by World War II. From 1924 to 1961, Amedeo Maiuri directed the excavations, uncovering large areas to the south of the Via dell’Abbondanza in Regions I and II. The clearing of debris outside the city walls revealed the Porta di Nocera and an impressive cemetery lining the road to Nuceria. By the 1990s, approximately two-thirds of Pompeii had been excavated, providing a comprehensive view of the ancient city.

More recent efforts have focused on conservation and preservation, as the exposed ruins face threats from weathering, erosion, and tourism. The Great Pompeii Project, launched in 2012, has aimed to address these challenges through extensive restoration work and improved site management.

In 1997, Pompeii, along with the nearby sites of Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This recognition highlighted the global significance of Pompeii as a cultural and historical treasure. The designation aimed to ensure the protection and preservation of the site, promoting international cooperation and funding for ongoing research and conservation efforts. The UNESCO status underscores Pompeii’s importance as a window into the ancient world and a source of valuable historical knowledge.

Today

Today, Pompeii is one of the most visited archaeological sites in the world, attracting millions of tourists each year. The site is managed by the Soprintendenza Pompei, which oversees ongoing excavations, restorations, and conservation projects. Advances in technology and archaeological methods continue to reveal new insights into the city’s history and its inhabitants. Efforts to balance tourism with preservation are ongoing, aiming to protect Pompeii’s fragile remains for future generations.

Pompeii’s modern importance lies in its unparalleled ability to educate and inspire. The site provides a tangible connection to the past, offering insights into Roman civilization that are both profound and accessible. Pompeii serves as a crucial educational resource, informing studies in history, archaeology, art, and architecture. Its preservation allows scholars to explore and interpret the complexities of ancient life, making it a cornerstone of classical studies.

The history of Pompeii, from its humble beginnings to its tragic destruction and eventual rediscovery, is a testament to the city’s enduring legacy. Through the dedicated work of archaeologists over the centuries, Pompeii has been brought back to life, offering a tangible connection to a world long gone but never forgotten. As excavations and conservation efforts continue, Pompeii remains a poignant reminder of the past, a source of knowledge, and a treasure trove for future generations to explore.

Leave a comment